Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

In the late 16th, 17th and 18thcentury, India produced luxury goods for the export to Europe and the world. Among those were precious gems, spices, fine textiles and inlaid furniture. The Portuguese encouraged furniture-making with mother-of-pearl, lac, and ivory in western India, whilst the British and the Dutch exported ivory-inlaid furniture from the Coromandel coast, in Eastern India.

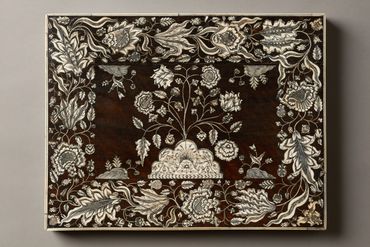

This dressing box or workbox was made in Vizagapatam, a port on the Bay of Bengal, halfway between Calcutta in the north east and Madras (then Fort St. George, now Chennai) in the south west. The port was home to travelling craftsmen, circulating between Madras, Bengal and the East Indies. It had a tradition of exporting ‘chintz’, painted and resist-dyed textiles produced in the region. These textiles that were the main reason for the European settlements and an English textile factory was established in Vizagapatam as early as 1668. However, the first reference to ivory inlaid furniture in Vizagapatam was made in 1756 when it is said that the place, known for its chintz, ‘is likewise remarkable for its inlay work, and justly for they do it to the greatest perfection’. This coastal region, the Northern Circars, was home to a ship-building industry and it is possible that the presence of European carpenters stimulated the cabinet-making industry. Many essences of wood used in cabinet-making: ebony, padouk, teak and rosewood, were readily available. The ivory probably came through trade from Pegu (Burma).

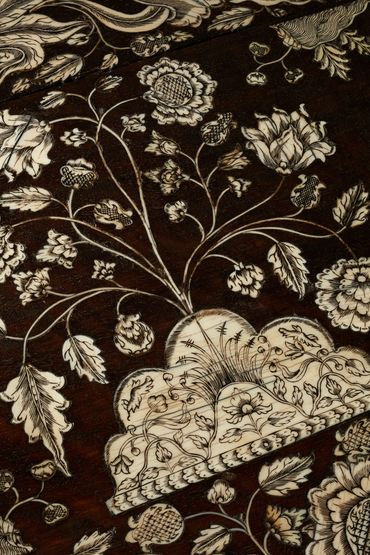

The furniture forms produced in Vizagapatam, or further north in Murshidabad, another centre for the production of ivory furniture, were often based on English or Dutch prototypes. The decoration however, remained purely Indian. It shared its decorative vocabulary with the chintz, a repertoire borrowed from the subcontinent’s luxuriant flora. Large, fleshy flowers and ripe fruits, attached to trailing meandering vines, flourish along the edges of bureau, tables and boxes. Large blossoming trees of life, such as the one on this box, are a central motif. Items made in the early part of the 18th century combine rosewood or padouk with ebony -where ebony is mostly used along the edges, with the ivory inlay. The use of ebony is progressively abandoned for that of a single essence of wood. During the 1760s to 1780s, ivory replaces exotic wood as the principal veneer and by the late 18thcentury Vizagapatam produces furniture entirely veneered in ivory. As such, this workbox is typical of the furniture produced in the middle of the 18thcentury: individual pieces of ivory are inlaid into the rosewood surface, whilst the engraved decoration is highlighted with black lac. The decoration is bold and painterly and there is no use of ebony.

Ivory furniture was produced for the English settlers and servants of the East India Company (EIC), the trade Company that came to control most of the Indian subcontinent during the second half of the 18thand first half of the 19th century. The EIC had a monopoly on the trade of many goods, such as tea, but never traded in furniture. The ubiquity of ivory furniture in British collections is due to personal initiatives: EIC servants having made their fortune in India brought them back to Europe, as testimony of their success in India. During the first half of the 18thcentury, this furniture is solely reserved to EIC elite. Edward Harrison (d. 1732), Governor of Fort St. George, is among the first to have purchased a bureau-cabinet, made circa 1720-30, which was sold at Christie’s in 2011 (The Exceptional Sale, 7 July 2011, lot 14 for £505,250). His successor, Richard Benyon, acquired a dressing-bureau between 1733 and 1744. It is now at Englefield House in Berkshire.

By the mid-18th century, ivory furniture becomes accessible to second rank servants of the EIC. Inventories for British settlers for the second half of the 18th century regularly list ivory and ivory-inlaid articles. In Britain, there was a developing interest for ivory carving and ‘Britons had a widespread desire to possess these exotic luxury goods’ -Margaret, second Duchess of Portland (1715-1785) is said to have taken up ivory-turning and Queen Charlotte, consort to George IV, had a passion for this type of furniture (Kate Smith, ‘The Afterlife of Objects: Anglo-Indian Ivory Furniture in Britain’ in The East India Company at Home, 1757-1857 – UCL History 1).

However, there are only a few important Vizagapatam items dating to before the 1760s, and they all belonged important figures of the EIC: Sir Matthew Decker (d.1749), a director of the EIC (1713-43); Edward Harrison’s (d. 1732) bureau, dating to 1720-30 (mentioned above); his daughter Audrey, Lady Townshend’s (d. 1788) dressing table; Richard Benyon’s (d.1774) bureau, Governor of Fort St. George (1734-44), now in Engelfield House, Berkshire, and Robert Clive (d. 1774), Clive India, dressing-bureau (NT1180668), at Powis Castle.

In her discussion of Indian ivory furniture through the 18th to the 21st century, Kate Smith suggests that they were ‘material manifestations of the empire’. The auction catalogue for the sale of Warren Hastings’ estate, sold long after his death in the 1850s, highlights on its opening page the ivory furniture from India. The many items of ivory furniture that are still today in British families tell the story of the long ties between Britain and India. These ‘anglo-indian’ narratives were inherited, down through family lines, or reconstructed, through the acquisition and purchase of ivory furniture in the 19th and 20th century. These items are part of a ‘narrative of empire’ (Smith, op.cit., p.26) and continue to be admired and collected today. In 2005, a large bureau-cabinet dating to circa 1740-50 and having belonged to Lily Safra, was sold by Sotheby’s for $1,472,000.

Photo: Matt Spour Photographer

Bibliography:

Kate Smith, ‘The Afterlife of Objects: Anglo-Indian Ivory Furniture in Britain’ in The East India Company at Home, 1757-1857 – UCL History 1

Amin Jaffer, Furniture from British India and Ceylon, A Catalogue of the Collections in the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Peabody Essex Museum, New Delhi, 2001

Of rectangular form with flat lid opening to reveal a fitted interior with open divisions, with long drawer in the front, the fine ivory marquetry with a painterly decoration in black lac of large flower and leaves, the lid with tree of life rising from a short mount, on four short feet

16.8 x 41 x 31.5cm.

Sold - Private Collection, London